In 1979, in one of the most cruel ironies of all time, the Iranian Women’s Movement played a crucial and powerful role in the Iranian Revolution that overthrew the Shah of Iran and established the Ayatollah Khomeini as the Supreme Leader of the country.

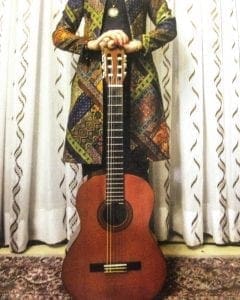

Narges 14 years old | Unexposed Wishes of Teenage Girls in Iran, Fery Malek-Madani 2017

In the years preceding the 1979 Revolution, the Women’s Organization in Iran had made incredible strides in women’s equality. By 1978, nearly 40% of girls 6 and above were literate; 33% of university students were women, and more women than men took the entrance exam for the school of medicine. Abortions were legal, women had equal rights in marriage and divorce, and equal pay at work.

The minimum age of marriage was increased to 18 for women and 20 for men, and polygamy had been practically eliminated. And women could stand for government office: 333 women were elected to local councils, 22 women were elected to parliament, and 2 served in the Senate. There were one cabinet minister (for women’s affairs), 3 sub-cabinet under-secretaries, one governor, an ambassador, and five women mayors.

Then it all changed.

Opposition to monarchical rule, government spending, and liberalization efforts (that didn’t sit well with more conservative members of Iranian society who felt the teachings of Islam were being ignored), started the first rumblings of revolution. Women’s organizations, by this time a powerful presence in the country, mobilized for revolution, too, throwing their support behind Ayatollah Khomeini in the belief that he supported and appreciated the power of women in Iran.

They were right — he did, but only inasmuch as they helped overthrow the Shah. Once seated in government, Khomeini began the process of reversing or dismantling almost every single right Iranian women had gained: veiling became obligatory; child marriage and polygamy was reinstated, along with stoning; and Farrokhrou Parsa, the first woman to serve in the Iranian cabinet, was executed.

The generation of women that grew up after the Revolution knew nothing of the freedoms their mothers and grandmothers had so briefly tasted.

Mina, 13: “I want to become the best writer.”

Mina, 13: “I want to become the best writer.”

Iranian photographer and filmmaker Fery Malek-Madani remembers. She was born in Tehran in 1955, was sent to school in Belgium as a girl, and enjoyed the same dreams and desires and distractions her European schoolmates did, plotting their adulthood with the world at the feet, driven by the same things teen girls have always been: balancing a need to save the world with making art with falling in love.

Malek-Madani stayed in Belgium, and has lived there since she was 11 years old. But after a lifetime lived outside of her home country, witnessing the revolution and the repression from afar, Malek-Madani found herself wondering if the girls in today’s Iran, post-Revolution and post-freedoms, have the same dreams as the teenager girls she once knew. So she went home to find out.

Unexposed Wishes of Teenage Girls in Iran is the realization of Malek-Madani’s dream. 40 photographs document the range and passion of teenage girls aged 12–16 in Iran, their visions for their future, both heart-wrenching and hopeful.

Assal, 14: “My wish is to see a world without war, a world full of friendliness.”

Assal, 14: “My wish is to see a world without war, a world full of friendliness.”

Malek-Madani conceived of a participatory project that would let Iranian girls’ voices be heard. Working with schools both in urban and rural areas, Malek-Madani and her team introduced students to the basic principles of photography, gave them all digital cameras and a single afternoon to photograph their dreams, the things that helped them realize their dreams, and the things that prevent them from doing so. They were also provided with notebooks, so the girls could explain their photos in greater detail.

The photos themselves range from photo-journalistic to pure artistry.

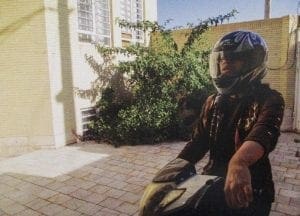

The girls are captured in moments of pure girlishness — flirting with themselves in the mirror, playing nurse with a little brother, writing poetry in the sun, perched on the ruins of an old house and relating that to humility in the way only 13-year-old girls can — and in moments of pure adolescence — on the sidelines of a soccer field, pulling faces on a motorbike, pouting and on the verge of tears while a parent reminds them of what they are not allowed to do.

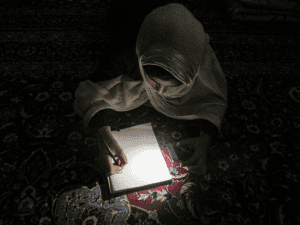

But in the most powerful photos, it’s the absence of the girl herself that defines her environment for us, the world her wishes are born in, and the world that puts obstacles in her way: a pile of stuffed animals, a neat line of shoes, a window with thick, iron bars.

Shamim, 13: “To have confidence in oneself and be motivated (like that little plant which will break the tiling to grow).”

Shamim, 13: “To have confidence in oneself and be motivated (like that little plant which will break the tiling to grow).”

The photos are accompanied by quotes from the girls themselves. They are not actually necessary, because the photos are clear enough. But they add an extra dimension of regular-ness or normalcy to the subjects, making them more familiar and normal. They’re just girls with dreams for their future, like every other girl, everywhere.

The documentary film The Girls that accompanies the exhibit is the photographs brought to life. Here are the girls in school, in living color, expanding on their dreams, their fears, and their frustrations at the status quo. Ms. Malek-Madani mentioned that she had not planned on making a film, but after meeting the girls and talking to them, she was so struck by how keenly aware they were of their discrimination, and how eloquently they voiced their objections and arguments for equality and the right to achieve their dreams.

Schoolgirls in Yazd | November 2016

And they are eloquent.

In one scene, a 11 year old girl stands up and gives an impassioned speech, enumerating all the points of inequality girls and women suffer in Iran on her way to proposing a more just balance of opportunity and quality of life. It’s equally beautiful that her teacher, instead of reprimanding her or telling her that nothing can be done about the status quo, simply states “that was a very well-articulated argument. You should run for Parliament!”

The desire for freedom of movement, be it physical or social, is palpable.

Across all the schools and all the girls who participated in the project, the desire for freedom of movement, be it physical or social, is palpable. Many girls wish to be doctors, because in Iran it is the only profession available to them that can move them out of one social class and into another, earn them a decent living and, more importantly, respect. But almost all the girls express, too, a longing for physical movement: in-line skating, swimming, soccer. Like teenage boys, their bodies are growing and they need to be stretched and pulled, their physical limits tested. These girls feel the restrictions of their clothing and their class painfully.

Shiva, 13 | “I hope one day to be able to ride my motorbike outside the house.”

Many of the girls participating in the project come from rural backgrounds, and Ms Malek-Madani had expected these girls in particular to be quieter, less ambitious, less aware of the gross imbalance of gender privilege. She was in for a surprise. Although their access to social media is regulated and limited, the girls from farming and working class backgrounds were often the most vocal, questioning everything and, as teenagers do, bucking against the system. Only their system is so restrictive, to move at all is to buck against it. And these girls are nothing if not full of movement.

Unexposed Wishes of Teenage Girls in Iran is on view until 23.5.2017 Monday to Friday from 9.00–18.00 at Landesvertretung Baden-Württemberg beim Bund, Tiergartenstraße 15, 10785 Berlin.

Find more information on Facebook and at Art Cantara.

Article by Susie Kahlich of Artipeous – Art You Can Hear